Resources

Some of Amy’s work with Tribal and Western environmental scientists, agencies, and researchers.

Please contact amy@myrbo.com with questions!

Download these one-sheet explainers for teaching or just to better understand some complicated topics:

If you’re looking for more in-depth explanations, please see the resources below!

This paper describes how Tribes and academic researchers in the western Great Lakes region have formed a fruitful partnership around manoomin/psiŋ.

Matson, L., Ng, G.H.C., Dockry, M., Nyblade, M., King, H.J., Bellcourt, M., Bloomquist, J., Bunting, P., Chapman, E., Dalbotten, D., Davenport, M.A., Diver, K., Duquain, M., Graveen, w., Hagsten, K., Hedin, K., Howard, S., Howes, T., Johnson, J., Kesner, S., Kojola, E., LaBine, R., Larkin, D., Montano, M., Moore, S., Myrbo, A., Northbird, M., Porter, M., Robinson, R., Santelli, C., Schmitter, R., Shimek, R., Schuldt, N., Smart, A., Strong, D., Torgeson, J., Vogt, D., and Waheed, A., 2020. Transforming research and relationships through collaborative tribal-university partnerships on Manoomin (wild rice).

Several peer-reviewed publications resulted from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s Sulfate Standard Study to Protect Wild Rice, conducted by Myrbo and others at the University of Minnesota.

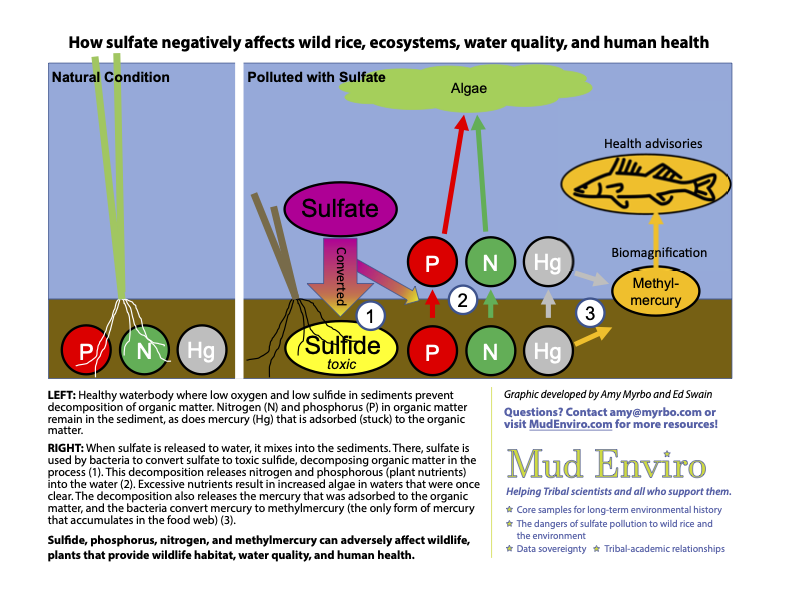

This trio of papers shows how sulfate is converted to sulfide, harming wild rice (manoomin, psiŋ) and posing other greatly underestimated risks to Minnesota’s environment and human health:

Myrbo et al. 2017a. Sulfide generated by sulfate reduction is a primary controller of the occurrence of wild rice (Zizania palustris) in shallow aquatic ecosystems.

Myrbo et al. 2017b. Increase in nutrients, mercury, and methylmercury as a consequence of elevated sulfate reduction to sulfide in experimental wetland mesocosms.

Pollman et al. 2017. The evolution of sulfide in shallow aquatic ecosystem sediments: An analysis of the roles of sulfate, organic carbon, and iron and feedback constraints using structural equation modeling.

And this publication shows how wild rice is affected by sulfate pollution:

Pastor et al. 2017. Effects of sulfate and sulfide on the life cycle of Zizania palustris in hydroponic and mesocosm experiments.

Recently Mud Enviro has been supporting Tribal resource managers to use “fossil” environmental DNA in core samples to understand the history and current distribution of wild rice (manoomin, psiŋ) in important lakes and rivers on-Reservation and on Ceded Territories to support conservation and restoration.

But first we held listening sessions with Tribal resource managers and Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPOs) to understand whether this method should be used by non-Tribal scientists and agencies, and if so, under what conditions and with what boundaries. This is the report from those listening sessions.

This work has been funded in part by the Conservation Paleobiology Research Coordination Network to our Working Group.